Jim Houser

By Shepard Fairey

Photos By Adam Wallacavage

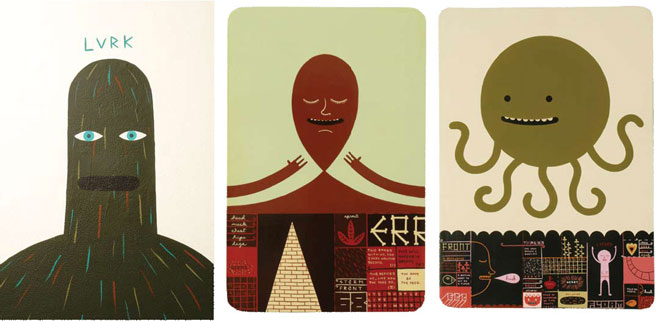

Illustration By Jim Houser

INTERVIEW FOR PRESERVATION PURPOSES. CREDIT DUE TO THE AUTHORS.

When Dr. Rorschach created his eponymous inkblots, I doubt he ever thought of them as works of art or considered him self an Impressionist. Still, he managed to build a tool that captured in its purpose what artists had already discovered: a viewers reaction to an image says as much about them as the image it self says about its creator. When I think of Jim houser and his art, I’m alway struck by the bond he consistently forges with his audience, the way every work of his shows me a piece of myself while at the same time reflecting his own catharsis. Jim’s paintings and installations span the entire spectrum of human emotion, but he never seems to pass judgment, leaving the bias up to the viewer’s discretion. Being Jim’s friend is synonymous with being a collector of his art – no one is more generous when it comes to requiting the admiration he gets from the people around him. The pieces in my collection all stand out individually, but there’s something about the gestalt of his installations, the way that each compartment melds seamlessly into the integrated whole, that creates an atmosphere of a bigger picture. Maybe that’s just my interpretation of it.

I met Jim in 1995 through Ben Woodward, a RISD student and a cohort in my Obey Giant/Alternate Graphics screen-printing studio in Providence, Rhode island. Ben had told me about his best friend from Philadelphia, a rippin’ skateboarder who was stuck in a security guard job and wanted a change of scenery. I offered Jim a job cutting stickers in the studio – the most tedious task we had, but he took it without thinking twice. That was one of the last jobs he ever held. He worked for me for six months, all the while progressing as an artist, and then spent a summer on Cape Cod, where he met his future wife, Becky Westcott, who always encouraged him to keep creating, even if it meant she had to support both of them. He moved back to Philly shortly after, where he became one of the founding members of the Space 10 26studio. He’s dealt with more than his fair share of tragedy and desolation, but he still embraces life with a pass ion that transcends all adversity. I’ve always admired Jim for everything he’s gone through to keep making art, and the fact that he’s still making art after all he’s gone through.

What were you doing before you came to Providence?

I worked in a parking garage in Philly, where is at in a booth and didn’t even have to take money – I just had to sit there. I drew and wrote for eight hours a day. And then I would go out and sit at This Denny’s right near my house and write and draw all night long. It wasn’t until I moved to Providence that is aw lots of rad stuff going on, and I was like, “I want to do rad stuff,” like all the stuff that was going on at RISD , and more so, all the stuff that was going on at your studio. The shit that you were doing, plus all the shit that was coming through there, whether it was just jobs for other people that you guys were doing, it was always something cool that someone made. The other thing was that you were always awe some, saying, “ Hey, I ’m going to New York for This art thing. Who wants to come?” You treated us like friends, not just your staff.

Once you were in Providence, the first thing I remember is that you were doing these cool doodles, and then you started filling in certain things instead of just leaving them black and white. The next time i saw your stuff, it was getting a lot more sophisticated, and you were doing the bottoms of skateboards. What happened in between getting to Providence and then painting boards?

I met my wife, Becky, and a lot of the time was spent with her. Being around her while she was painting made me want to do it and experience what she was getting out of it.

Was that the summer where you and Ben Woodward worked on Cape Cod?

Yeah, we talked about it in my book, Bab el. We were living out on Cape Cod with nothing to do, and we were working like 10 hours a day,so we found some paint. Ben had a shelf with checkers, dominoes, and paint. So it was like, well we could either get really good at checkers, or we could make pictures. Then I met Becky, and I was going to her house twice a week on my days off. Her mom gave me real paint for my birthday.

And a month later, you were painting on boards.

Yeah. When I first started playing with paint, I filled a sketchbook with paint. I painted in the sketchbook pages. I filled a sketchbook, which is like four inches fat. When I had that, is tarted painting on pieces of wood, boards included, and just started painting pictures. Five a day, ten a day – I just painted all the time. I worked at This coffee place where, if I had to work there for eight hours , I’d do what I wanted to do for eight hours too. I just never slept.

Would you say skateboarding fueled your creativity?

Totally. ‘cause it was art. It was something where you can make stuff up by yours elf. When I moved to Providence, it was the first time is aw the connection between human beings and the art on skateboards. Before that, the skateboard was something that you bought at a store and it already had a rad picture on it. The thought never occurred to me that someone out there was making those.

I remember after I moved to San Diego, it must have been ‘97 or early ‘98, you sent me a packet of photos of all your work, and there were so many boards and paintings. I couldn’t believe how prolific you’d become.

It’s so easy if it’s all you do. If you’re like, “Alright, This is all I’m going to do now,” I don’t care what it is , you’ll get a shit load of it done.

When was the first time a stranger came up to you really interested in what you were doing? When was the first time it really clicked that other people outside your circle could be interested in this?

I don’t know. I remember getting really stoked about it just from the input that I was getting from my friends. I had so much respect for people like Adam [Wallacavage], for example, just for telling me when he thought my stuff was good and encouraging me to keep doing it. I had so many paintings, anyone who came into the realm I was painting in and picked something up and said, “It’s cool,” I was like, “It’s yours .” I just gave away everything. Everyone already had one before they even realized they wanted one.

At that time there were so many people around all the time, like in the Alternate Graphics realm. And it was like, “If that idiot can do it, I can do it.”

You make stuff that will work with the culture you’re down with. That was back when all of a sudden skateboarding was no longer being completely ignored in terms of creativity, and you actually had an opportunity to do something. That’s really motivating.

For me it’s also a function of making shit out of who you are and what you’re doing, and a function of poverty, not having any money. So many boards passed through my house. I’ve also pulled the fronts off all the basement stairs of every house I’ve lived in, and painted those. Everything around me gets painted on.

It’s cool that you’re feeding back into that cycle of creativity in skateboarding by doing what you do, doing stuff for Toy Machine and other skate companies. The next 14-year old sees it and will be stoked.

The coolest thing is seeing a little kid with one of my boards. The way I look at it, that kid went into a skateboard store where there was a wall of skateboards, and he thought mine was the raddest one. I remember getting my first board when I was 11, and I had that feeling of buying that one skateboard and being like, “This board is sick.” To me it’s so rad.

Do you remember anyone encouraging you to draw when you were a little kid?

Everyone. I don’t remember anyone ever saying, “ Don’t draw.” From when I was little, my parents always encouraged me, and so did my teachers, though maybe they were like, “ Don’t draw during class. But This is good.” I never had someone tell me not to do it.

What was your thought process in making art a career and not having to do other stuff?

After every show, there’s always been another show, and I’ve always sold at least half of my stuff. After a while, like two pretty good shows in, is till had a job, and I thought, “This is retarded.” So I quit my job in 2000. But I was part of a team. It was Becky and me. She was working sometimes. She was always like, “I’ll be going to work if we need money. I want you to paint.”

Your shows have some great art progression, from paintings to skateboard ramps and bigger things, where they have become more than a collection of paintings on a white wall. They interact with the characters that you create in a painting, then you bring them to light on the wall and build 3-D shelves and all other kinds of fun things. What was the evolution of that?

Seeing people like Ed Templeton and Chris Johanson,seeing the way that they made little pieces of art. Like they both make little art, or used to, at least. I was drawn to that. I really connected with the way is aw them and Margaret [Kilgallen] and Barry [McGee] use a gallery space, making their little pieces of art into big pieces of art. Not on the level of their subject matter, Because in some cases I don’t connect at all, but just the idea of turning a bunch of little things into one big thing that you stand back from and it makes sense. i started painting thinking of the individual paintings working across several pieces of art. I want the whole thing to be one big thing that you look at.

When you sit down and paint, do you sit down and say, “This painting would look very cool if the wall were painted blue, with an octopus behind it.” Or do you just sit there and make your body of work?

I just sit there and make pieces of art. And I never plan it, ever, till I get to the space and I have a basic palette of colors to work off of. I look at the walls and I just start. I make it up as I go along. Then I arrange the individual pieces of art so that it all makes sense.

In your imagery, it doesn’t seem like there’s a logical language you’re trying to create. It’s almost like this Rorschach association thing.

It’s definitely associative, more than anything else. And the things I paint repetitively are pictograms to me. In my head they have meanings, but I can’t sit here and say, “This means This , This means that,” Because some of them have corny explanations. But they work, visually and emotionally, for me.

Anyone that looks at it is going to come up with their own thing.

People put their own shit on my paintings. They interpret things however they want to. Some dude rolled up on me, and was like, “ Yo, you were molested when you were little, weren’t you?” And I was like, “ No, but you were.”

Do you like that, though, as an artist, that people have their own meanings for images?

Well, that’s like another express ion that I always use. You have your concept of Mom, and I have my concept of Mom That’s the way all back and forth is. So no, I don’t care how they interpret it.

What determines your word choices? The way you design your type is really awesome, and sometimes I wonder if there’s a connection to the imagery or whether it’s just a word you think is going to look good.

I went through This insane period where I wanted to get really good at looking at text and seeing instantly how many letters were in it. I wanted to be able to read and be like, “3, 5, 9, 1, 7, 5.” I wanted to be able to see how many letters there were, just from a design element. I thought of really cool ways, at least to me, of breaking down words and sentences where they read poetically and work visually.

I’ll always say that text in painting is cheap. The reason is Because the classic idea of a good painting is a painting where your eye moves thoroughly through the whole painting. There’s no other easier way to get peoples eyes to go from left to right than putting down text. So you can fix broken areas of painting with text.

So you’re a cheater?

Yeah, I am.

You have music incorporated into your current show.

It was the third time I did it. I’ve been playing music for 10 years. I have no musical background. I just listened to punk rock and wanted to play it too.

What made you want to pick it up and play it?

This guy Craig, who is till play music with, had a guitar and changed the tuning pegs on it, and it wouldn’t stay tuned. He tried to tune it, got pissed off, and put his foot through the sound hole. I was like, “Are you fucking crazy?” He was like, “That thing sucks.” And I was like, “If I can get it fixed, can I have it?” He said yeah, and a friend of mine fixed it up and it became my guitar with a massive hole in it.

But for this show, you created music to go along with it.

The whole installation is a map of all the music that’s been going on in my head over the last four months. That’s all the music I made during the same period And the two go together, ‘cause I made them. Everyone who’s creative is probably creative on multiple levels. With music, you’re checking out how different things fit together, and I go through almost the exact same process when I’m making art. It’s cool. It’s just a different way of doing it.

What’s the meaning of the title of the show, “This Place is Ours Now,” and how did it come about?

Becky’s ashes are on This beach in Nantucket where she grew up and where her mom and dad live. It’s a little beach with a lighthouse on it. That’s where we decided, if anything was ever going to happen, that’s where we’d have our ashes scattered. My mom and I have gone down there, and hang out all the time. It’s This insanely beautiful piece of real estate on This insanely expensive is land, and you think about what it would cost to buy. I was talking to my mom, and I was like, “ Because of what we did here, we own it. This place is ours now. No one can say This isn’t ours here.” So that’s where the name of the show came from, that concept, going through that with somebody, experiencing something so raw with someone that wherever it happened, you now own it.

Frankly, it also has to do with the other side of that: the title of the show is like my ego. I took This place over, for me and my friends and family – it’s mine now.

Your work is either very celebratory or super dark and depressing, but it’s all treated equally. It’s kind of reassuring, in a way, that everybody’s got their ups and downs. I’m curious about your process of coming up with both the happier stuff and the bleaker stuff.

It’s a function of who I am. I am literally like that, and it varies from the kind of stuff that comes out, the day-to-day, and certain things that I think up during these periods. Like if I think of 20 things, one of them might catch on and stay with me for a while, regardless if they’re things that seem happy or things that seem sad. They’ll travel with me and get repeated over and over again for a given period of time. I didn’t have them all at the exact same minute. There are times where I’ll think about life and realize it sucks. I am fucked up Because of what I’ve gone through. But there are other times where I can’t complain; I’m here. It goes back and forth like that. That’s why there are things that seem super, super happy and things that seem super, super sad.

What do you want the viewer to get out of what you’re doing?

I didn’t really think about it until I made an installation and stood back from it, and felt really calm. Like, wow, looking at This thing I made calms me down. And then after making that realization being like, “I wonder if that calms other people down?” That’s good. So I want the viewer to walk in and get calmed down.

I think just to digest the whole experience of your show, there’s a lot there to soak up. It’s pretty intense. It’s amazing to just look and take it all in on several levels, from the individual paintings to the individual compartments and elements of the paintings. I think it’s rewarding for viewers purely on a formal level, and a lot of other artists have never been able to do that. I’m not saying that you have a duty to communicate a specific message or anything, I’m just curious.

I guess what it is , and it sounds corny, but when you feel things and you go through stuff, for me as a person I want to talk about it with people. That’s how I am. If something happens to me, I’ll tell you. I’m like the biggest complainer in the universe. And I think every thing’s wrong with me. If somethings going on, I want to let people know. I like to communicate what I ’m thinking and feeling with my paintings and art. To me, it’s important enough to put it out in the world. Like, “Hey, This is what I’m going through. This is life for me. This is the one I’ve got.” So I ’m going to show it off. This is me just trying my best.

As an artist, what do you want to do, what do you want to see as a progression?

I don’t know. I’m in such a fucked-up place I can’t even think about that. I’m just getting by. That’s all I’m doing. I’m making a living doing what gets me through the day