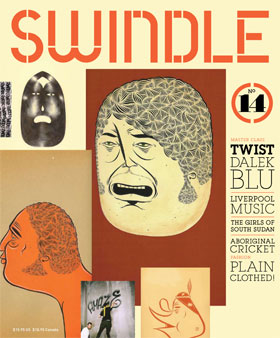

Barry McGee; TWIST

By Andrew Jeffrey Wright

Photos By Dan Murphy

FOR PRESERVATION PURPOSES. CREDIT DUE TO THE AUTHOR.

Other artists blazed the trail that brought graffiti from the urban landscape into galleries. But no street or graffiti artist who came before Barry “Twist” McGee had executed the transition with such finesse. Born in San Francisco in 1966, a city he continues to make his home, Twist began painting graffiti in 1984 at the age of 18. He began showing his work in local galleries, slowly building a following, and, in 1991, he received a Bachelor of Fine Art in painting and printmaking from the San Francisco Art Institute. This was quickly followed by grants and fellowships—one notably sent him to Brazil, where he observed clustered framed artworks displayed in churches. McGee incorporated this presentation style into his art shows, which brought a kinetic, urban immediacy to the staid gallery space.

As he earned an increasingly prolific presence in the “established” art scene, Twist continued to remain relevant to the street art movement. He was featured in the prestigious Venice Biennal in 2001, and now, his work often sells for hundreds of thousands of dollars. His immense popularity has helped legitimatize the street art genre, paving the way for superstars like Banksy and SWINDLE’s own Shepard Fairey. And still, he hits the streets with his illegal graffiti, where his pieces rarely get painted over by other artists—though city cleaning crews frequently buff over his work. As his work in galleries rises in value, his work on the street is considered an eyesore by the general public. This is an irony that seems to fascinate Twist. As he told PBS’s Art 21, “There could be a rooftop that is just sitting dormant for a while, and someone goes up there and does an amazing piece of graffiti… And that is removed and two months later there’s a huge billboard over the whole spot anyway.” In 2006, Twist fell into some controversy. He worked with Adidas to create a limited-edition shoe, emblazoning it with a “Ray Fong” caricature of a buck-toothed, bowl-cut Asian boy. Asian- American groups accused Twist and Adidas of being “racist.” It was picked up in the international news. Finally, in defense, Erik Nakamura, one of the founders of Giant Robot sent a mass email pointing out that Twist is half-Chinese American, and the Ray Fong image was a depiction of the artist as a young boy. Twist was silent through all this. He hardly ever grants interviews—and lets his work speak for itself.

In a 2002 article on the “Mission School” of Bay Area artists in the San Francisco Bay Guardian, artist Amy Franceschini said of Twist and his wife, fellow street artist Margaret Kilgallen—who sadly passed away weeks after giving birth to their daughter in 2001—“They are very per ceptive, noticing every curve in the road, every inch of a street.” A hallmark of Twist’s artwork is his zen-like understanding of composition and context.

Philadelphia-based artist Andrew Jeffrey Wright has collaborated with Twist on ‘zine projects and gallery shows. Here, exclusively for SWINDLE, the notoriously private Barry McGee opens up to a fellow artist.

You have a remarkable surfing ability. When I surf with you I see you catch wave after wave, only paddling two or three times to catch a wave. How long have you been surfing?

I started my senior year of high school in 1984. I was really into riding BMX at the time, but had an accident messing around on my Cooks Brothers. I broke a femur bone. I was loosely interested in skateboarding and I had a subscription to Skateboarding, but mid stride the magazine turned into a hybrid of sorts: Action Now. It had BMX, skateboarding, surfing, sandboarding—all those things combined with music of the time. I remember I was in the hospital, in a cast, reading this magazine, and thinking surfing might be a good thing to get involved in. As soon as I was out of that cast a friend and I were cutting out skimboards in woodshop class.

Did you go right to long boarding or did you do short boards first?

I had a friend that I started with, Manny Miranda. We were both in high school together. I bought a used 8-foot Local Motion surfboard, and he bought a 7-foot-6 Seatrend, and we just learned surfing that way. We went to Rockaway Beach, it was the first place we tried. It was the closest beach to our high school that our car could make it to. We tried for a long time. It’s a fairly hard sport to learn in crappy conditions and cold water.

You had no one teaching you, you just went out there?

We just kept on going… and a few weeks later we started standing up. I remember getting up and riding waves pretty OK and as soon as that happened we decided it was time to get the latest short boards of the time, after about two months. We traded in the used boards and got a 6-foot-2 Bessell Quad and 5-foot-2 Stussy Quad.

So you were out there every day for two months?

Yes, but our learning curve went downhill really fast after that. We went from catching waves to sitting around a lot in the ocean trying to catch waves.

Eventually you took a big road trip down to South America in a van or something like that?

Yes, in 1988 we drove to Central and South America in a ‘71 Volkswagen bus. It started off as just a surf trip, driving as far as we could. We brought $1,000 each and that lasted a year. We had 500 of it in travelers checks, and somewhere around the eighth month we “lost” our travelers checks. It was the first real trip I took. I was 21.

Tell me more about what the 1980s were like for you. I heard you were in a scooter crew or something like that?

I was into scooters for a little bit. It was a good scene—skinheads, punks and transgender artisttypes. Ronald Reagan was our president at the time.

You just drove around the city poppin’ pills and picking fights with rockers?

Pretty much.

Did your scooter crew have a name?

No, there were some guys I hung out with that did graffiti and rode scooters—this guy Ken Bowen and Zotz. That’s how I got into graffiti; Zotz was the one who handed me the spray can. He’s the first person that said, “Barry, lets go… it’s time to catch tags.”

What was your first graffiti alias?

I wrote Twist. There was this scooter magazine at the time called Twist, so I took that name.

This was in 1982?

No, ’85.

1985? That means I was doing graffiti before you.

You did graffiti pre ’85? Were you breakdancing too?

Yeah.

OK, you win. You must have did [sic] it when we were really young. You need to be secure with the dates, though. Like when you do graffiti, you put the date after it. You should have wrote, “Comic Kid 1980.”

Before Zotz handed you the can, did you even think about graffiti?

Well, growing up I remember seeing the classics, such as “W.P.O.D.” and “smoke weed.” As a youth my grandmother lived in San Francisco, and we would always go to her house on the weekends. There was this tunnel, the Broadway tunnel, and there was a pig somebody spray painted at the end of the tunnel.

And that put the seed in you?

I don’t know, I remember seeing it and couldn’t figure out why somebody didn’t like pigs. The word “fuck” was painted above it. I knew what the word fuck meant but I didn’t know cops were pigs. It probably took like a year or two to figure it out. I knew it was weird. I often wonder what my life would be like if this piece of graffiti history wasn’t in my childhood.

When you did start, did you look to anybody for stylistic inspiration?

Oh certainly, there was a guy who used to write “Plato” from Oakland.

And you liked what he was writing?

No, it wasn’t so much what he was writing, he had this character next to his tags. Plato had all kinds of tags up, and next to his tag he had this Don Martin style character with a big hairdo. Zotz had a cowboy fellow inside his “o.” So I just assumed that you were supposed to put a character with your tag or integrate it with it. Shit, this was the ‘80s anything was possible…

Like the drawing of the dude with the hat and the beard and a nose…

Uh—yes—it was supposed to be a skeleton, but you just look at the walls and know that that’s Zotz, that’s Plato. They stood out from the plain ol’ tags on walls of that time.

Where’d your character come from?

I’m not sure… Some parts came from the Rat Bones logo.

It’s like a wiener dog with a lot of legs and a sweater. Is that the first thing you did with absolutely no words, just an image?

No, I used to write something with it—like “Kingpin” or something. I was spray painting all kinds of weird stuff then… I think I wrote “Disarm,” “MDMA” and “Slam” around that period.

What’s MDMA?

Like, a drug.

Is that a drug you would take?

It was an early form of ecstasy I think.

You took ecstasy in the ‘80s?

I think so…

But right now you’re pretty much straightedge?

I am?

Yeah, you don’t do stuff.

I tried to drink a beer last night.

Tried to? What happened? Did it disintegrate before it touched your lips?

No, I drank one sip out of it. I don’t know what happened to it afterwards. I think it got poured into the sink.

Are you half straightedge still?

Oh goddamn. I hate that stupid movement or word or whatever. I mean, I don’t ever try to preach anything to anybody—except total anarchy and chaos—but no, I don’t smoke or drink except one sip of beer every three years to prove I’m American.

So you were born and raised in San Francisco?

Yes, born in S.F. I was raised in South San Francisco, a suburb. I really enjoy the San Francisco lifestyle. It has graffiti that is specific to San Francisco—like the bus hopper style, it’s been around forever. There are all types of freaks here, which keeps it interesting all the time. It’s a small city, and you can get around on a bicycle. There’s a good energy here, like no other place that I have been.

Graffiti is no longer just spray paint on a wall. I’m just curious what you think the next innovation will be?

I can only assume it’s just going to get bigger. Entire skyscrapers covered with gigantic tags. At least that’s what I hope for.

I noticed, not because I was looking, but because I have peripheral vision, you don’t wear underwear. Do you own underwear?

I do. I wore underwear maybe three times this year, once in prison.

Because it’s kinky now when you wear it?

No, I don’t know why. It’s just another thing that gets in the way.

I wear underwear all the time, feels great. So you had a scooter ‘zine in the ‘80s?

I did. It was called Bump Start or Jump Start. It had a lot of pictures of scooters, messed up ones, choppers and stripped-down racers. I remember an article with the Morlocks, an advice column with Walter Alter and a guide to which pills to dance all night long on.

Did the graffiti element get involved in these?

Yes, it was starting to. BBS was a great scooter gang that bombed the muni yards hard—Boast, Beast, Up, Jarski. Did you do any ‘zines?

Yeah. When I was a kid, this one tough kid we used to hang out with wanted to name our skate ‘zine The Underground Skate Mag, and we thought it was really redundant because obviously it was an underground skate mag. He was just too tough for any of us to be like “We don’t like that name,” so that was the name of our ‘zine. The first issue had a lot of skateboarding in it, the second had a little less, by the third issue, it was just all jokes and goofy collages and just making fun of each other. It lasted like four, five issues. I remember one time we used the church photocopy machine; our youth group leader let us use it.

Were you still Christian then?

Yeah, I mean, the underground economy plays a huge part in the survival for poor people and for things that are just overpriced. Even if you come into money, you still want it for free. It’s outrageous. The one thing was, I was never good at stealing. So even when Kinkos had all those things, like you could take a paperclip and hi-jack the machine, I would sit there for 20 minutes liberating photocopies with a red face and just waiting to get caught.

I think you stole some reams of paper didn’t you?

I prefer to call it liberating. I can liberate some paper ‘cause that takes three seconds, but to sit there for 20 minutes to an hour just ripping copies… I remember a worker coming up to me, I thought I was so caught, he just came up to me and was like right up in my face, and my face was already beet red, and he was like “Can I help you with something?” and I thought I was totally nabbed, and I was like “Nah, I have everything under control,” and he was like “OK, well you just let me know if you need anything.” I was like, “Oh my goodness.”

Have you ever been caught for graffiti?

Yes, I got caught spray painting a derogatory statement about our commander in chief.

How long of a run did you have before you got caught?

I had a pretty good run—it wasn’t until 2004. You start to get sloppy when you get older. I did my eight hours of community time, cleaning up some New York parks. Very rewarding and enlightening experience.

In past conversations, I’ve heard you say how you’re done with a certain artistic element in your gallery shows, and how you’re going to make this drastic change. But all the changes within your gallery exhibitions and art are really incremental. How come occasionally you want to do this drastic change but it never happens?

Dammit, Andrew, I’m a doctor not a miracle worker. I think change will come some time. It takes me a long time to change.

So you went to art school. Did you ever have any shows that were within the school? Like your senior thesis show?

You had to give a proposal for a show, and I did a few shows. It was just like junk all over the floor, drawings, paper, stuff I found on the street. It looked like a squat.

Did your installation resemble what Jonathan Borofsky was doing?

Well yes, somewhat, papers all over the floor. I had seen his work in slides or a lecture in art school. I like his work, it’s accessible. It doesn’t hurt my head looking at it. I met him a few years ago. He was really nice and engaging. I told him we used to have discussions about him in art school.

So then after you get out of college, how do you segue into doing commissions for people outside?

I was just doing graffiti, and working as a printer. I was in art school trying to figure out what that was about. I didn’t know what that was about. I still don’t know what it’s about. But I was trying to figure out how these people can magically make something and then earn [a living]. It seemed like more of the art than the actual art.

Did you ever go through a period where you’re sending in slides to people and trying to get them to look at stuff?

Oh sure. I only sent my stuff to people who asked. I never felt desperate enough to send slides to every silly gallery in town, working the system. For grants, I would do the dance for sure, but only if I was approached by them first. That sounds like dating

So then which came first? I know you did outside pieces legally that were paid for by cities and stuff, right? Art commissions. Were you showing in galleries at that time? Is that how they knew about you?

The Luggage Store, a non-profit, was the first gallery that asked me to do something indoors, Laurie and Darryl. I think they saw some of my work on the street, and they invited me to show some work [there]. And I was like “That sounds great.” Through them, a lot of other shows happened at other non-profit and alternative galleries.

You’re working on a publication now, right?

Yes, it’s just getting started. It’s called Jesse’s Day. It’s about three straight white males and then Clare and I. It’s gonna have Jesse Gellar, who is from Philadelphia, you and Dan Murphy. It’s going to be 11 x 17 folded, and the covers are going to be 120- color silkscreen. It’s going be highly political, yet provocative, with a feminine touch.

So I read in a past interview of yours, this was a while ago, that the next thing you wanted to do was huge tags on the front of museums. Then I saw a photograph where you did a huge tag on the front of a museum, just like you said you were going to do.

Yeah, that was in Detroit at The Museum of Contemporary Art. They said, “What would you like to do with the museum?” and I asked them if I could do a huge throw up on the front. They said, “That sounds great.” I then asked Josh if he would do a huge fill in on the building, and he agreed. It took 178 cans of silver to fill it in. I think it’s still there. To remove it, it will cost $1500.

That’s it?

Yeah, a bargain in today’s rapid economy.

Then what are these people complaining about, this whole property damage thing?

I have no idea. It’s not them that’s complaining, it’s the advertisers worried about graffiti infringing on their space.

One of the things graffiti unintentionally does is make up new places for advertisers to put ads. I remember, on the sides of phone booths, there were never any ads there, and then people say, Oh there’s graffiti there, that’s where we can put our ads. I know you were approached once to make some art to go on a perfume bottle and you said, “No.” Then you were approached to do some art on a billboard that has a Nike logo on the bottom and you did that. What is the theory behind what you will say “yes” to and “no” to?

Uh, the money. It was $8,000 to put a piece up there. It didn’t really look like “my” work. It was just a photo of RYZE doing a tag. I think if someone looked at that, they wouldn’t go, “Oh that’s a Barry McGee photo.” Where[as] if I did something for CK1, anything to do with a bottle, they still wouldn’t know it was a Barry McGee, but I would know. Would you do art for an alcohol company?

I think I’d do it. Yeah, just not cigarettes and porn.

Would you do it for the army or recruiting? ‘Cause I’m sure they want hip ads.

That would be a serious dilemma. I wouldn’t do it for less than $50,000. I don’t even know if I would do it for that much. I don’t like guns, and I guess I’m a pacifist. I feel like one. But, yeah, I don’t know if I would do that. So the army, cigarettes and porn—I wouldn’t do any drawings for ads for them.

How about Pfizer?

I would. Erectile dysfunction—I would do art for any drug dealing with that because the commercials are really funny. I guess when it comes down to it, it’s not as cut and dry as I would like to think it is. Do you have to turn down a lot of commercial work?

It depends on how much I need money that month. Sometimes it works; sometimes it’s embarrassing.

So you don’t watch television. Was there a point in your life where you just said, I’m going to cut the TV off or did you just grow up thinking this isn’t that interesting?

After high school, I went to junior college. I took some art classes. I had a teacher there, he was a bit of a hippie, he had his synopsis of what was going to happen throughout the semester, one part was reducing your television intake. A lot of the things he said made a lot of sense. He was just this kind of normal hippie guy, teaching a class at a junior college. I started thinking this teacher is encouraging students to try things that are as radical as anything in the United States. These are all things that Americans do, they sit at home and watch television, they go into work the next day and everyone talks about what happened on Taxi—that’s one of the last shows I watched on television, sorry.

When you started taking art [classes] and realized that’s the direction you were going in, did you ever have a backup plan in case it didn’t work out?

Yes, I learned to be a printer. I worked at a print shop, a letterpress shop. They did gold foiling, embossing and die cutting. That was my back-up plan. I used old antiquated machines for high-end architecture firms, letterhead and such. It was really popular for a while. I had a really good boss who was a touch new age and a vegetarian. He taught meditation, staring at your eyelids. He was great, Norman Hicks.

You never worked on any screenprinting or anything like that?

I did some screenprinting in college, but I’ve always been more into machines. I’m fascinated that it could just take your finger off in a split second.

I got my art school scar here on my pinky. Do you have an art school scar?

Well, yes, mental scars. This one too, look. Someone had a dog in the printmaking department, I went to pet it and it bit me.

What kind of dog was it?

It was a small one.

I noticed you don’t have a website. Is there reasoning behind that?

I don’t know, I don’t even know what I’m doing. I don’t know if this is right or not, but I’m getting the same feeling about computers as I did with television. It’s just so wildly popular, and all of America is just taken by it. I think it’s necessary for what I do a lot of times. I’ve done a lot of communicating and stuff like that, but I don’t like it. It doesn’t feel natural.

So in five years, that’s when you want a website?

I hope to be entirely removed from society by that time. Off the map. Checked out. You want my Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television by Jerry Mander?

Yeah. Is it a book?

Yeah, it’s a book.

Oh, I thought you were just going to rattle them out.

No.

Does it come on video?

No, it’s only on television. I’ll give you my copy, really.

Do you have anything in mind that you are going to do differently? What’s the next step?

I’m going to get all my stuff framed, like normal frames, and I’m going to hang them all up in a commercial gallery in a perfect line, 53 inches high with proper spacing. I think I can do it.

Are there any artist or artist friends of yours that you’re excited about that no one really knows much about?

Jesse Geller. He’s living his life the way he likes to. Jesse—I like his stuff. His mind works in a good way. He lives in San Francisco. He moved here from Philadelphia. There’s this homeless transvestite, an Inuit Indian, that hangs out at Walgreens by the studio, and he brought him/her a nice jean jacket, and painted the back really nice, and just laid it by the bush where the person sits, not even thinking about it, and a matching hat with it. Alicia McCarthy is a really good artist, Adek, Chris Lux, Aaron Curry, you, Bill Daniel.

Did the transvestite wear the jacket?

She hasn’t been spotted with it.

I think this is the end of the interview. Do I have a last question?

You don’t have any questions. You ran out of questions a long time ago.