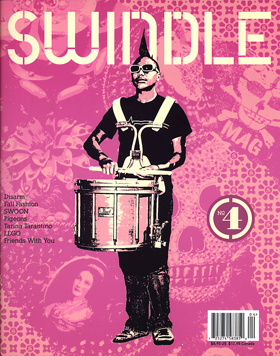

Swoon

By Marc Schiller

Photos By SWOON

FOR PRESERVATION PURPOSES. CREDIT DUE TO THE AUTHOR.

Countless artists take to the streets each day and integrate their imagery into the city landscape, but few have achieved the level of reverence and respect given to Brooklyn-based artist SWOON.

SWOON has the rare ability to not only use the city as a canvas, but to transform it while doing so, making the grayness of city walls and doors recede into the background as her characters take center stage. Over the years, her dedication has never lessened, and her work on the street has become more intricate, more complex, and more thought-provoking.

For us, the city of New York and the artwork of Swoon will forever be linked, much like the work of Holzer, Basquiat, and Haring before her.

It seems that not a day goes by that someone doesn’t ask us the inevitable question: “So, who is your favorite street artist?” And while we try to pass the love around and not play favorites, our answer is always SWOON.

On Growing Up in Florida

I spent my childhood growing up in Florida in a small town in the country. My best friends all had horses and cows and there were always a million kids around. And then when I was 10 years old, all at once my friends suddenly grew up and moved away. For weeks, I would wander around the yard not having anything to do. My mother said to me, “You’re always drawing. Why don’t you take this class that I know about. It’s for adults but I’m sure that they’ll let you in.”

So, at 10 years old I went to this painting class that was for older ladies who needed a hobby. I was the only kid in the class. But this great and extremely kind woman was teaching the class. And I loved having a teacher to show me how to do things. So when I brought my first art piece home, everyone started to freak out. They couldn’t believe that I had made it. It was a transforming moment, because at 10 years old I realized that I could actually make things that people liked.

I began hearing people throwing around words like “child prodigy.” And I started thinking that maybe I really was a genius. But it was totally not true. The paintings were pretty good but not unbelievable. The most important thing was the confidence it gave me. I was completely sure that painting and drawing were what I wanted to do and, more importantly, what I could do. From then I started drawing and painting on everything.

On Leaving Home at 17

I was 17 years old when I left my hometown to go to an art school in the Czech Republic as an exchange student. People where I lived thought that I was completely out of my mind. But my parents knew that the talent I had was not going to blossom in the small town where I lived. After the Czech Republic I went to New York to study at Pratt. My mother’s attitude was “Get to New York and everything will start to make sense for you.” She knew.

On Moving to New York

In the beginning I was into classical painting, and would read lots of biographies of people like Michelangelo. I was very serious about what art was and what it was not.

But when I started taking classes at Pratt I suddenly felt a strange tension, an angst about the way that artists are “created” in art school. I realized that becoming an artist was all about getting a portfolio together and understanding how to approach the galleries. It felt like I was being herded into this very small space. And my reaction was “I’m not going in there!” And at the same time my painting wasn’t really going anywhere for me. I didn’t really like realism all that much. I felt that, from a technical standpoint, anyone can make something look real. But once you reach that pinnacle and you can make something look real, it’s not that exciting. For me, it became more about redefining myself as an artist than learning to make my art more realistic.

There was this one day in painting class when I had a mini freakout. I set my brushes down and had this realization that I couldn’t do it anymore. I needed to give up everything that I had learned and start over from another place. Another viewpoint.

On Her First Influences

The work of Gordon Matta-Clark was a real kick in the head for me. Matta-Clark was using the city itself and then re-creating it. At the same time, I became interested in a few people who were putting art up on the street. I knew of REVS, Shepard Fairey, WK, and a few others. A friend of mine at the time had to explain to me that what Shepard and REVS were doing was actually art. At first, I thought it was advertising or something. I didn’t understand it. But once I realized that it was art and it was being placed into the context of the city by the artist, it all started to make sense. So then at school I started to make my first series of block print posters. The whole process of printing the poster was a way for me to get away from everything I had been learning at school.

Studying in Amsterdam

After the meltdown, I ended up moving to Amsterdam for a semester to get away from everything. I would go to the library every day in Amsterdam. I pored through tons of books. I became very interested in this idea of reflecting the city back onto itself. I lived on a sailboat and I made no friends. I was living on four dollars a day and went to the library all of the time. I was definitely searching for something. I was reading all of the time. Things like The Situationist City and lots of books by Rem Kohlhaas. I became obsessed with thinking about cities and the concept of impermanence a lot. I began thinking about things that were part of our daily lives but couldn’t be removed from it because they couldn’t be bought or sold. I became very upset about the commodification of everything that I saw. I knew then that I couldn’t make the kind of art that I was seeing in the Chelsea galleries back in New York. I felt a need to find a way to make art that couldn’t be owned and presented in that way. So while I do make objects for galleries now, I came to figure out how to do it in my own way.

Returning to New York

When I got back to New York from Amsterdam, I had all of these paper posters printed from the blocks I had made. I knew that the pieces were for the streets. It was the first time I had ever done any work on the street and the posters looked horrible. The paper I was using was beautiful, but it was also extremely thick. It wrinkled really badly when I pasted it to the wall. The whole project was a big failure. But because I had failed, I became very determined to get it right. I then started doing work on billboards and did a lot of poster collages.

At the time, I was living on Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn. Every day there was a new street-level billboard on my street. And I hated them all. But I also realized that they were so low on the street that I could actually reach them. A giant light bulb went on in my head, and I went back and made these giant paintings that I then glued completely over the billboards to cover up the advertisements. I wanted to make something that would make people question why it was there in the first place. Advertising is always asking you for something. And I wanted to make something that was completely ambiguous and wasn’t asking anything from anyone.

On Becoming SWOON

My boyfriend at the time was very influential in my work. He was born and raised in Manhattan and we were both in love with the city. He woke up one morning and said to me, “I had this dream last night that you were a tagger and you wrote the name SWOON. We were running from the police and all I could think about was how beautiful your name was.”

Later, when I started doing a lot of work on the street, I remembered the name SWOON from his story. I had also read about a time when a woman would wear corsets so tight that she would pass out. They romanticized it and called it a swoon. It was as if the moment overtook her. But in reality she passed out because she was wearing restrictive fashion. And I thought that it was good that women have evolved to a place where we’re not doing this to ourselves anymore. I look at the word SWOON as a body of work, not as my name. SWOON is not me. I’m not Swoon. SWOON is like a way of thinking. It’s a body of work. It’s a series of interrelating thoughts.

On the Creative Process

I always start with photographs. I take hundreds of them.

Usually one or two will pull me in emotionally. I like to capture in my work the exact moment when someone realizes that I am looking at them. When I start a piece I first take the photo and think about how it can best be represented in my work. Sometimes it will lead to doing a woodcarving. Sometimes it will lead to being a paper cutout. Sometimes it’s linoleum for getting lots of tiny lines. I always choose the image first and the medium second. And then I make sketches and go from there.

On Becoming Part of the City

It was only last week that I first realized that through years of working I had actually made a mark on the city. Before that, I felt strangely anonymous, like I was doing these things that were being put into the flow and was being sucked down river like everything else. But now I’ve received enough feedback to know that my work is actually affecting the city in a very specific way.

On Dedication and Commitment

I know that people respect the extreme commitment that I put into my work. It’s sometimes hard for people to understand how I can spend so much time on a piece and then put it up on the streets where it can be gone so quickly.

At first, I was precious about everything and wanted my work to be permanent. And because I knew that it wasn’t permanent on the street, I wasn’t putting all I had into my work. But then something happened where I stopped caring about permanence and started putting everything I had into the work. At that moment, everything changed for me. It all came from a cutout portrait I did of my grandfather. Because it was of my grandfather, I gave everything I had in making it. And when I finally finished it, I put it up on the street and never felt happier. And the amazing thing I learned was that the work that I put the most into seemed to last the longest. For example, the portraits I did of my grandfather lasted over two years on the street. Today, my commitment to the process of creating art for the street only grows stronger. People are now seeing less of my work in New York only because I’m putting more into the work that I’m actually doing.

I like my artwork to have a lifecycle. I’ve done paintings using stencils. But for me the paintings don’t do anything. They just stay there. But in working with paper, as I do now, the pieces become alive. It’s organic. The paper curls. It ages. It rots. It’s responsive.

On Working in Galleries

I feel like for me, the gallery is a whole different thought process. Even though it’s the same body of work, the thinking behind it is very different. It doesn’t work for me to take what I do on the street and then simply move it into the gallery. It’s not the same thing. I made this mistake a few times. The good and bad thing about the street is that it demands so much from you. Because there are so many limitations, you have to come up with a lot of solutions. But at some point, I realized that I could think differently about the galleries. For the gallery work, I started thinking about things that could benefit and take advantage from the use of a roof. I started using materials that I couldn’t use outside. So while my gallery work is related to the street work, it’s actually a whole new thing. For me it’s about creating these crazy cities that are in my head. I like the fantastical aspects of the city; the magical qualities.

Not having to suffer the burdens of reality. I love the book Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. Lately, I’ve been obsessed with utopic failures. For me it’s about going so far into your imagination that the whole thing keeps collapsing over and over again. But the important thing is not that it works, but that you keep dreaming and dreaming. I think that when I get inside into the gallery I want to show you part of my brain. The gallery door becomes the front door into my brain.

On Earning a Living from Art

Selling my work for the first time was very strange for me.

Here I was selling my work at prices that me and my friends could never afford. But because my work is so labor-intensive, the work that people buy has to be at a high price. So I had to let myself understand that when people buy my work they are also supporting other things – mostly my street work. Because there are people who can afford to buy my work, I use some of the money to create the same work, only I put it up on the streets so that others can have it for free. I want my work to be part of people’s daily lives. I want people to have it for free. So if you have it in your house, you are also supporting people having it on the streets.

On the Future

I don’t know where things will go from here. I’ve been working in this way so long that I’m not dreaming about new things that much anymore. I’ve now done so much of the things that I used to dream about. So now I need to find new things to dream about. I need to re-center and figure out what I want next, because right now I actually don’t know what I want next. The street is still important to me, but now it’s about human connections on the street. I can see myself changing focus.

On Doing Commercial Work and Working with Brands

I feel like I do the work because there is a certain experience I have in mind when people see my work. I want them to experience it in a very specific way. And if I did commercial work, the experience would shift and it wouldn’t be mine to control. It would be in the control of the brand. I make human-sized portraits because I want someone to walk up to it and feel that there is another human presence there in my work. I’m in control of the experience. There’s always something in my work for people to connect with.

I try to do the right thing politically, environmentally, and socially, and unfortunately many of the companies and brands that are the hottest in hiring young artists are also the most destructive and irresponsible. I think artists bear some responsibility to ask a certain amount from the world around them. As artists, we’re creating symbols and we need to lend these symbols to the right things and to the right people. Companies need to be asked tough questions. They don’t need us to blindly support them by lending them our credibility.

On What’s Next

My work is an Old World skill. I can draw and I tell stories. And so I’m starting to ask myself what stories out there need to be told. I want to know what stories are not being told strongly enough or loudly enough. I’m starting to wonder if there aren’t places and people who could use the skill that I have. I feel like with my skills as an artist I have this tiny little megaphone. I want to find people who need that megaphone and make a difference in the world with them.